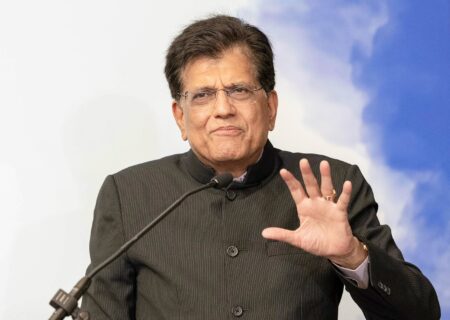

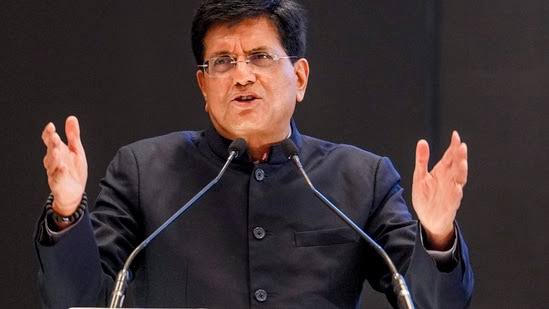

Minister Goyal emphasises no EU trade deal if the dairy sector is included, protecting India’s $132 billion dairy market.

India’s proposed Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the European Union (EU) could face substantial delays as the Indian government firmly resists opening its vast dairy market to foreign competition. Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal, speaking at the 18th Asia Pacific Conference of German Business in front of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, underscored India’s commitment to safeguarding its $132 billion dairy sector, which is central to millions of rural livelihoods. According to Goyal, any FTA that includes preferential access to India’s dairy sector would not be viable, given the sensitivities surrounding this critical industry.

The EU’s push for preferential access to India’s fast-growing dairy sector has been a point of contention in negotiations. Goyal highlighted that much of India’s dairy industry is made up of small-scale farmers with a few milch animals, making them especially vulnerable to large foreign dairy companies. “I just can’t open up the dairy sector. If the EU insists on it, then there will be no FTA,” stated Goyal, signalling that a trade deal would only be possible if both parties respected each other’s sensitivities.

The Indian government has historically been cautious about liberalising its dairy industry in trade agreements. In recent FTAs with Australia and the four-nation European Free Trade Association (EFTA), India maintained strict controls on dairy, including import duties of up to 68% on dairy products and rigid compliance standards, effectively rendering dairy imports unviable. Since 2011-12, no substantial imports of dairy products like skimmed milk powder (SMP) and milk fat have been allowed, helping shield the industry from international competition.

India’s dairy market, valued at $131.5 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $291 billion by 2033, growing at a CAGR of over 8%. This market size, combined with the fact that India is the world’s largest milk producer, has attracted significant interest from the EU. However, India’s dairy industry is highly fragmented, with small-scale farmers operating within a complex supply chain that has evolved to cater to local needs. The sector plays a crucial role in rural employment, further complicating the prospect of foreign competition.

Goyal emphasised that India’s sensitivities stem from stark contrasts in income and development levels between India and the 27-member EU. Unlike in EU countries, where dairy operations often include large herds, Indian farmers typically rely on smaller-scale farming with only a few animals. This dynamic, Goyal noted, would make it difficult for domestic producers to compete with foreign companies. “You are 27 countries, each with different priorities. India has 27 states with their own unique needs. We may be able to reach a fair trade agreement if each side respects these factors,” Goyal remarked.

At the conference, Chancellor Scholz expressed optimism that the India-EU FTA could be concluded “in months rather than years” if both sides worked collaboratively. He affirmed that his government is eager to progress swiftly with the FTA, which resumed negotiations in June 2022 after an eight-year hiatus. Despite nine rounds of discussions, Goyal acknowledged that the ongoing negotiations require political direction and should not be left solely to bureaucratic processes.

Adding to the complexity, the EU’s initiatives, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and Deforestation Regulations, introduce rigorous standards on carbon emissions that directly affect trade flows. Goyal suggested that such issues should be managed through international frameworks, allowing FTA discussions to focus primarily on trade, investment, and strategic partnerships.

While Goyal recognised the potential for an agreement if both sides respect sensitive sectors like dairy, the road ahead remains uncertain. The FTA would mark a significant milestone in India-EU relations, fostering deeper economic ties, yet it hinges on mutual compromises and a shared understanding of each economy’s unique dynamics.